At EiM, we are on a mission to have a positive impact on the planet and society through education. Central to this is staying abreast of the latest education research and developing the approaches and programs that will best prepare our students to navigate the increasingly complex world we live in.

"There's no point in learning a foreign language these days: everybody speaks English internationally, and even where they don't we've got Google Translate."

You've heard this before. You may have said it yourself. If languages are just about communication, then Mandarin will only be relevant to those who will need to communicate directly with Chinese speakers without relying on human or digital interpreters. But a growing body of research, as well as our own experience, suggests that communication is not even the principal value of learning a foreign language like Mandarin and this has implications for our approach to language provision in our schools.

Up until now, the primary arguments for including foreign languages in the school curriculum have all been based on the importance of being able to communicate with people from other nations or backgrounds in our increasingly multi-cultural cities and globally interconnected world. Mandarin has been rising to the top of the pile because of the sheer size of the Chinese population and the economic power of the nation.

There are two pervasive assumptions: firstly, that languages are about communication; and secondly that they are in their own vertical, alongside other curriculum subjects like Maths, Biology, and Geography. The first assumption leads people to conclude unless we can communicate clearly, or if the other side speaks English, our language learning is worthless. The second assumption leads people to conclude that, since we all ultimately have to focus on a handful of verticals and let the others go, then language learning is really for a minority of specialists and of limited value to the majority.

Language is the stuff of thought

By contrast, the work of Stephen Pinker and others challenges both of these assumptions. They argue that language is first and foremost the means by which we process ideas, and only secondarily the means by which we communicate. That means that understanding even some of how a language works broadens our repertoire of thought patterns and thus improves our thinking skills. The more language we are familiar with, the more equipped we are to find solutions to unforeseen problems which require fresh thought processes.

In the digital age, students can find out any information, anytime, anywhere – more quickly and in more depth than by asking their teacher. What students need today is not to memorise information that may or may not prove useful to them in the future, but to develop the skills needed to process information as they find it. Language skills comprise the most fundamental elements of that skill set. Thus, language learning should not be regarded as a vertical alongside other fields of study; rather, it should be seen as a horizontal foundation that is a prerequisite for the study of any subject. Our ability to fully explore any subject area creatively will be expanded or limited by our linguistic ability.

There is also a growing body of evidence to suggest that learning other languages is a key ingredient in our cognitive development and well-being. It would seem that because different languages process ideas differently, using different languages exercises our brain and keeps it healthy - even staving off the onset of diseases like Alzheimer's. Dr Thomas Baks of the University of Edinburgh and Dr Dina Mehmedbegovic of University College London thus advocate adopting a "healthy linguistic diet". Just as exercise is important for our physical health regardless of whether or not we are "sporty", so linguistic exercise is important for our mental health, whether or not we are "good at languages" .

Mandarin equips us to navigate the modern world

When it comes to brain training, Mandarin is supremely valuable because it operates so differently to Indo-European languages like English. For example, in the English sentence "I see her", there are three concepts: me, another person (who is female), and the activity of looking. If I rearrange those concepts into "She sees me", then all three words morph into different forms. The forms are so different that there is nothing to suggest that "she" and "her" refer to one and the same person; neither "I" and "me". The English language prioritises the role of a concept (that is, is the person the subject or the object of the action? Is the action being performed by the speaker or a third party?) over the concept itself (this person, that person, looking). By contrast, in Mandarin, the labels for each concept do not change because the concepts themselves do not change, even if they interact in different ways. Thus, "I see her" is "我看她" and "She sees me" is "她看我": the same words, just in a different order. The language we use changes our viewpoint and our focus, even when we are thinking about the same thing. The ability to shift perspectives like this is a key to critical and creative thinking, and studying foreign languages – especially Mandarin – is where we can learn how to do that.

If Pinker et al are right, then Mandarin is human beings' most popular means of thought. Do we really want to be ignorant of that as we face the challenges of the modern world? Do we want our students to miss out on the thinking skills of 20 per cent of humanity?

Implications for our school classrooms

This reframing of what foreign languages are for calls for a radically different style of language provision and pedagogical approach in the classroom.

When approaching a new language, typically the first thing we want to know is "How do I say 'two beers please'?" (or something similar) because we think that learning a language means learning how to tell others what we want. But if we are trying to build a relationship, protect ourselves, negotiate with someone, or sell something across borders, then the most important thing is to discover what the other party wants.

Anyone who has tried conducting a meeting through an interpreter will know how disconcerting it is not to be able to read the air or make sense of what is going on behind the words that are being translated. The value of learning another language today then, where translation is so readily available, lies not so much in being able to understand what others are saying as in what they are thinking. This understanding enables us to see ourselves and our own problems from a different perspective, as well as enabling meaningful, empathetic engagement with others. In which case, we need to shift the focus of our language classrooms from encoding what we already know to decode whole worlds that we do not yet have access to.

It is common for business people to say they would like to be able to read a newspaper from a country where they want to do business in order to understand their target market. If we adopted the standard encoding approach we are used to, we would recommend they start with a beginner’s course, progress to an intermediate, and move on to an advanced. Five years down the line, if they are diligent in their studies, they may be ready to tackle a newspaper.

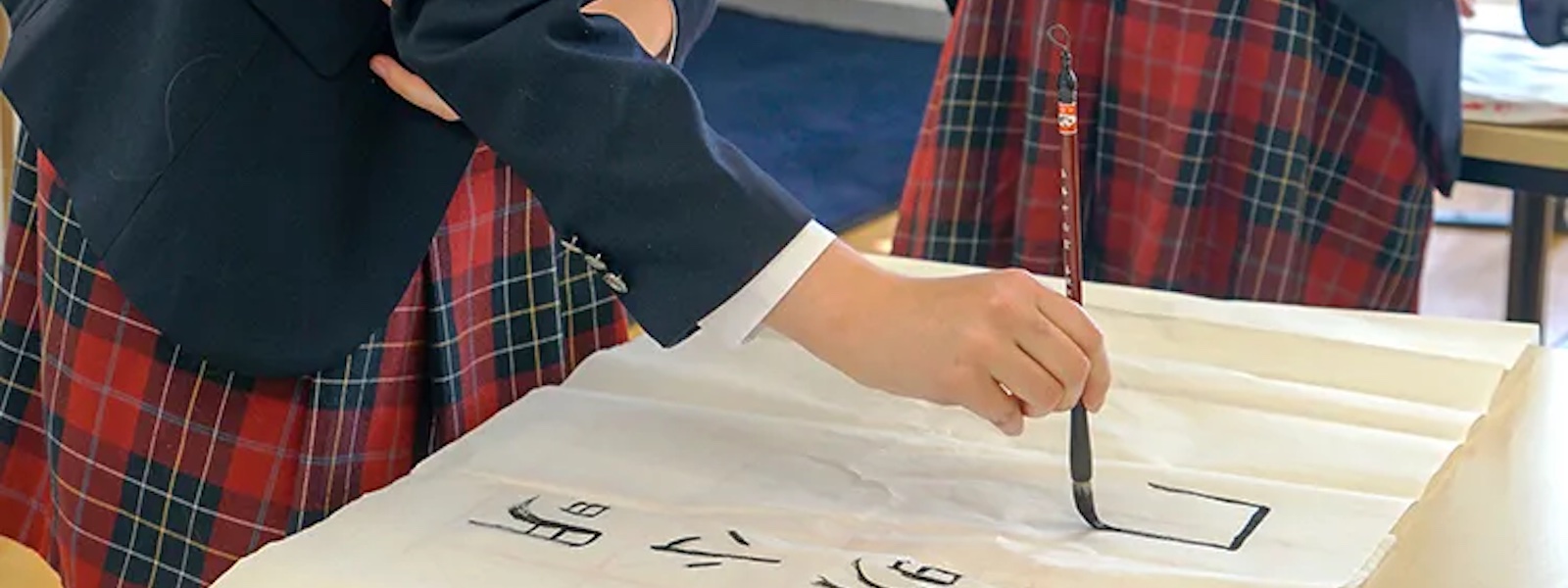

On the other hand, if we adopted a decoding approach, we would place the newspaper in front of the person immediately and ask them to study it to see what they could deduce. Even with a Chinese newspaper, students will quickly spot numbers, punctuation and paragraphs that help them to discern the structure of the page. They will work out references to dates and sums of money. They will conclude that Chinese words all fit into equally-sized square boxes which can be stacked either horizontally or vertically. They will start to identify patterns and recurring symbols. Tell them that 中 shows a box with a line through the middle and consequently represents the idea of "middle", "central", "core" or "China" and they will excitedly hunt down scores of occurrences of that character.

The sheet of paper that just minutes earlier was an opaque and disquieting barrier has been transformed into an intriguing new frontier that they have begun to make some sense of by themselves. It is as if a little patch of the misted window has been cleared. In the process, they’ve started to build the skills and confidence they will need to navigate other unfamiliar situations and to find solutions to any new challenges they will face in the future.

Our inter-connected world has become increasingly fractured. As members of a global society, we desperately need to find gateways through the walls that we keep erecting. The "great wall" between the English – and Chinese-speaking worlds is one of the most visible and obvious. If we can find gateways through this wall, we can be confident of being able to find gateways through any wall. This is why language learning in general – and English speakers learning Mandarin in particular – matters now more than ever.

Wo Hui Mandarin, one of EiM's brands, enables learners of Chinese to use their language to "navigate the world with confidence". Wo Hui puts the learning of Mandarin Chinese into the hands of the student and empowers teachers to support them on their personal learning journey. Recently, the company was appointed the first official provider of HSK Examination Questions and have developed the official HSK MOCK platform in partnerhip with Chinese Testing International.