How can we improve the limitations of a traditional ‘industrial’ education to keep up with a rapidly changing modern society?

In this article, Dr. Kevin House, Education Futures Architect at Education in Motion (EiM), proposes an shift in our systems towards regenerative education.

Education at scale has always come at a price. Often, it prioritises a didactic approach to teaching and a passive approach to learning. Student-teacher ratios require that students sit in quiet attention as knowledge content is delivered by a teacher at the front of the classroom before carrying out uniform tasks that are evaluated using standardised assessment. Paulo Freire once described it as the "banking model" of education because knowledge and skills are mapped, accumulated, and assessed like the profit and loss columns of a financial ledger.

The trade-off with an industrial education model is that we value perceived efficiencies in knowledge dissemination over the quality of the learning experience and development of soft skills. What’s more, the pool of knowledge has expanded rapidly over the last half-century without much thought given to reviewing the curriculum due to technological advances in content access. Moreover, our economy of scale worldview does little to promote learner agency (Bandura 2000), which has been shown to enhance independent thinking, initiative, and self-direction. Is it any wonder that future of work think tanks identify a global soft skills deficit when our dominant model of education does little to develop them?

How we learn is as important as what we learn: how we learn as children affects how we behave as adults. Today, we face a host of complex environmental problems, yet suffer from societal inertia and constantly look to 'experts' for solutions. Indeed, the expert has become the adult proxy for the classroom teacher, and our inertia towards 'wicked problems' stems from a passivity learned in school.

To address this learned behaviour, education must provide environments and experiences that promote more agency, collaboration, and interdisciplinary approaches to knowledge and skills development. In future, learners must constantly road test their burgeoning academic knowledge by applying it to immersive, real-world challenges rather than the abstract scenarios traditionally used in classroom task setting. Additionally, future learning must build soft skills fluency by providing far more authentic experiential opportunities beyond the classroom.

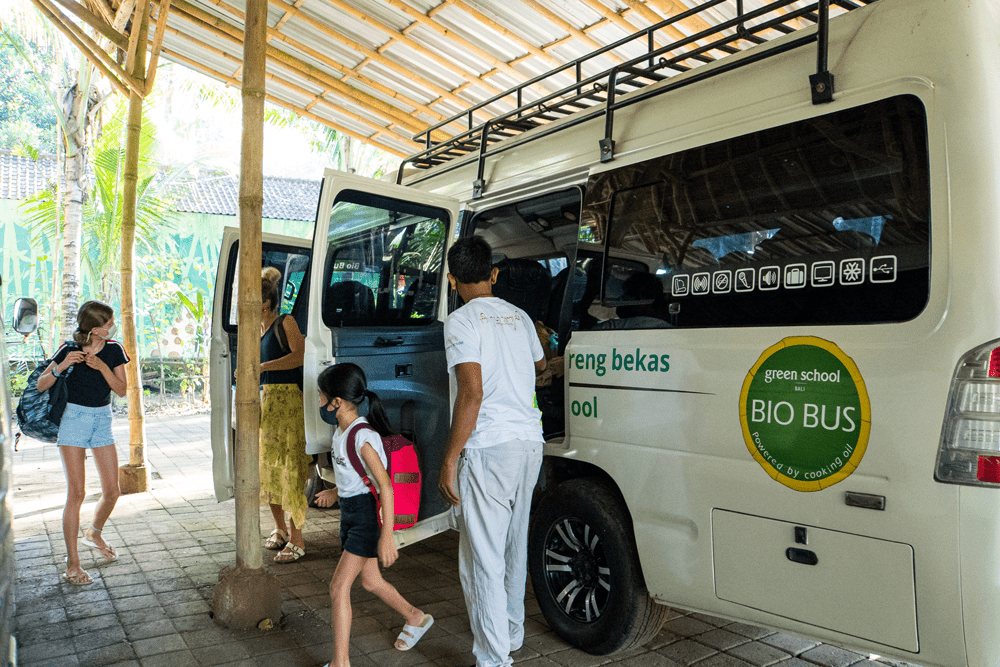

One example of such an approach can be found in EiM’s Green School, Bali, when students objected to the use of polluting diesel fuel in the school bus and sought to find an alternative solution. While exploring this issue some students also noted that many local restaurants disposed of used cooking oil in the open sewage system. Both activities were having a detrimental impact on the local environment. By learning about complex systems relationships and recycling science the students were able to research and design a solution to both problems.

The project culminated in what has become known as the Green School Bali Bio-Bus. Students now collect used cooking oil from local restaurants and use a student-designed recycling process so that the cooking oil can be used to fuel the school bus. The project was student-driven (agency) and required impressive soft skills to bring the local restaurant owners onboard and raise funding for the recycling apparatus. Importantly, it applied academic knowledge to solve an authentic real-world environmental problem.

Redesigning industrial education

At EiM we have been examining how to redesign the cluttered curriculum inherited from the industrial education. Much of the research and development grew from the SE21 high school concept that was developed between 2019 and 2021. In that work we created a literacies framework model, which has informed two school models within the EiM network: Green School International and School of Humanity. Each took the principles of the SE21 literacies framework and created a version reflecting their own approaches to learning design.

For School of Humanity, the Human Literacies Framework (HLF) addresses the problem of complexity in learning design by establishing a model that acknowledges two fundamental principles of future-ready education. First, the HLF recognises the iterative nature of knowledge and skills acquisition and the regenerative reality of a challenge-based curriculum. Second, School of Humanity’s framework articulates conceptual domains and knowledge dimensions in ways that actively prioritise an interdisciplinary approach to learning design. Having said this, the literacies model is not intended as a replacement for good examples of traditional educational practice, rather it represents a reengineering of existing knowledge areas alongside the incorporation of new and emerging disciplines.

Green School International takes a regenerative approach to accelerate systemic transformation in education. Its aim is to better equip learners to meet the needs of the twenty-first century than traditional approaches. The model ensures curriculum convergence across Green School’s global network by mapping its learning outcomes to internationally recognised qualifications frameworks. The foundation of the curriculum is articulated in the Green Literacies Framework (GLF), which acknowledges established disciplinary learning whilst anticipating a more interdisciplinary learning future. Together with the Green Skills and I-RESPECT values Green School International’s curriculum appreciates what knowledge and skills traditions we must have while anticipating how new knowledge and skills priorities are developing as our future evolves.

Why literacies?

It goes without saying that by the end of school most of us describe ourselves as literate. It is, however, an outmoded view of literacy. Today, society requires us to be more than fluent in reading, writing, and mathematics. With the advent of technology and the proliferation of text forms we now must be literate across a wider array of textual, aural, and visual media. Furthermore, we need a more sophisticated understanding of applied numeracy because our lives are dominated by data.

Recent approaches to learning design often use one of three common concepts when describing the what of learning: and these are competency, capability, and mastery. However, an audit of these terms reveals there is little agreement on what each one describes. One way of understanding them is to see each on a skills continuum. At one end there’s competency with capability somewhere in the middle, and mastery at the other end. Seen this way, competency somewhat underplays the depth of knowledge, skills, and dispositions acquired at school whilst mastery is maybe too presumptuous for a high school learner. Finally, capability is perhaps too suggestive of a deficit approach to knowledge and skills accumulation.

Both School of Humanity and Green School International see literacies as a better way of describing every student’s varying fluency and sophistication across disciplinary knowledge, future-ready skills, and sustainable values. Moreover, the term is informed by three powerful theoretical uses of the concept that effortlessly align with a future-focused approach to education.

The first conceptual influence on the literacies approach is 'critical literacy', which describes skills developed by students through Freire's 'critical pedagogy'. Literacy seen this way offers 'an important strategic, practical alternative for teachers and students to reconnect literacy with everyday life, and with an education that entails debate, argument, and action over social, cultural and economic issues that matter' (Luke and Woods 2009). In other words, critical literacy equips learners with a sophisticated awareness of the political realities of both how they learn and what they learn. Most importantly, a literacies framework not only nurtures the skills required to navigate relevant ideological and economic debates, but also builds the agency needed to create effective solutions.

A second inspiration for the literacies draws on Cope and Kalantzis' theory of 'multiliteracy' developed with the New London Group in the 1990s. Multiliteracy represents 'a set of supple, variable, communication strategies, ever-diverging according to the cultures and social languages of technologies, functional groups, types of organisation and niche clienteles' (Cope & Kalantzis 2009). It is essentially the ability to read across disciplines and media using various interpretative methods and communicative tools. Significantly, multiliteracy is interdisciplinary in nature thus making traditional disciplines permeable and open to transdisciplinary concepts connecting across knowledge domains.

Finally, the concept uses three inter-related literacy models that have emerged in regenerative educational theory over the last thirty years. 'Environmental literacy', 'ecological literacy', and 'ecoliteracy' are used often interchangeably to describe educating for a more environmentally aware and agentic citizenry. Again, using the term literacy emphasises an interdisciplinary approach because it is ‘open and inclusive, and… involves the overlap and interaction between subjects of study… and ways of knowing (Berkowitz, Ford, Brewer 2004). Essentially, ecoliteracy synthesises traditional and new knowledge taxonomies, evolving human skills maps, and contemporary dispositional priorities. In other words, being ecoliterate means fluency in traditional and new knowledge domains, twenty-first-century skills, and environmental dispositions.

Regenerative education

A curriculum built around a literacies framework anticipates the dynamism of modern learning and the fluid nature of knowledge and skills development in a rapidly changing world. In Green Schools and School of Humanity we understand that powerful learning arises by 'weaving between different knowledge processes in an explicit and purposeful way' (Cope & Kalantzis 2009). To this end, the literacies move beyond the limitations of the competencies-capabilities-mastery continuum because they identify for future learners a broader map of knowledge, skills, and dispositional traits. The literacies concept offers students a timely and authentic learning experience, which builds future adults not hamstrung by the inertia of our generation. EiM's development of literacies frameworks in partnership with Green School International and School of Humanity represents a judicious regeneration of traditional learning's value proposition, and an invitation to reconsider education's higher moral purpose in these testing times.

References

- Luke and Woods 2009

https://eprints.qut.edu.au/27520/3/27520.pdf - Cope & Kalantzis 2009

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15544800903076044 - Berkowitz, Ford, Brewer 2004

http://www.sendadarwin.cl/espanol/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/ecological-literacy-alan-berkowitz.pdf - OECD 2019

https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/contact/OECD_Learning_Compass_2030_Concept_Note_Series.pdf - Bandura 2000

https://scalar.usc.edu/works/ismdia-590-community-data---s2019/media/Bandura2000.pdf